He was a man of integrity whose political and economic positions often flowed naturally from that very fact.

Read MoreHe Could Have Been President

He Could Have Been President

By Lawrence W. Reed

Across the 60 presidential elections in America since 1788, hundreds of people have formally campaigned for the office. We should be glad that most of them never darkened the front door of the White House.

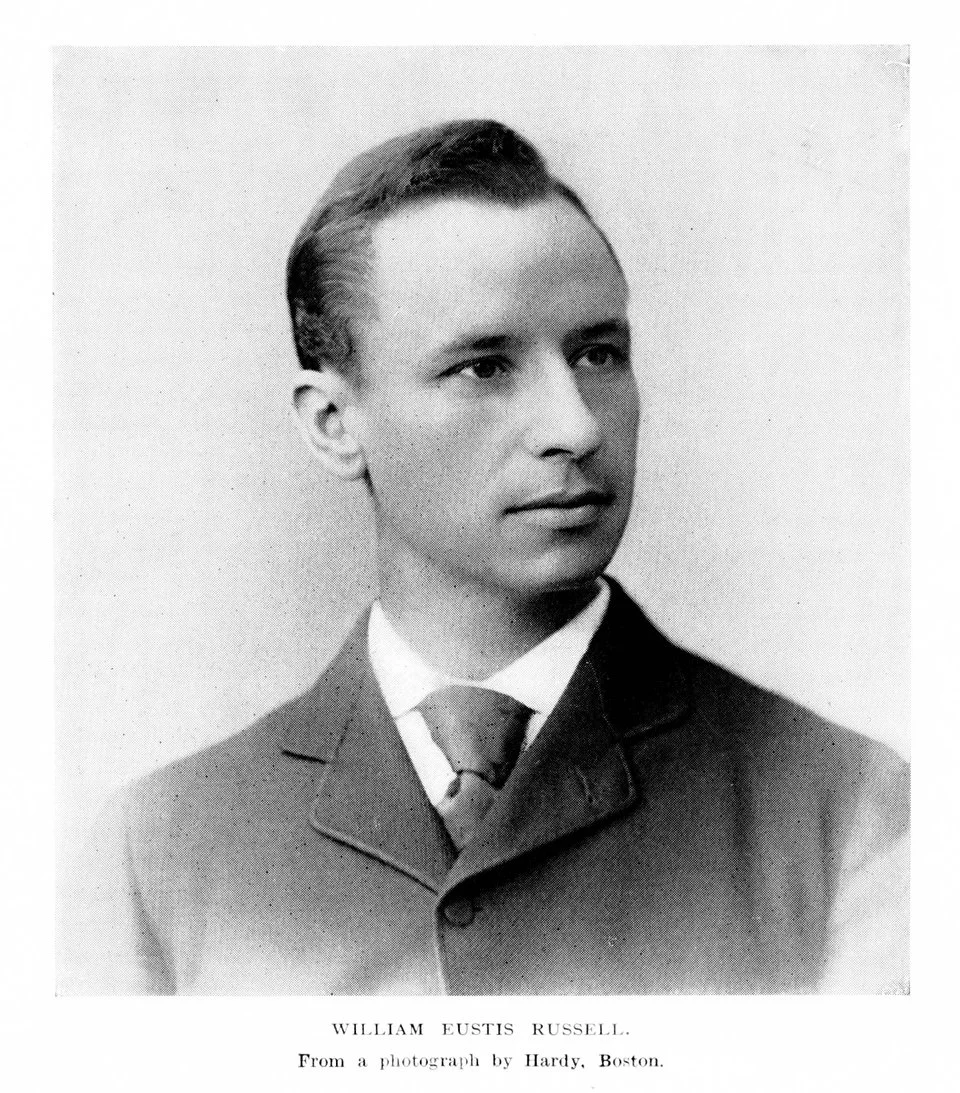

Some of those who didn’t make it might well have become very good presidents. One such man was William E. Russell of Massachusetts.

Born in Cambridge on January 6, 1857, William Eustis Russell earned his undergraduate degree at Harvard University, then picked up a law degree from Boston Law School, graduating as valedictorian of his class. He was popular with his classmates, not only because he was bright and friendly, but also because he was a charming, good-looking man. He became a successful and respect lawyer in 1880. He was widely regarded as sincere, honest, amiable, and a pillar of good character.

Those traits showed up in his convictions about politics and economics. A Democrat in the mold of Grover Cleveland, he championed small and clean government, low taxes and low tariffs, and sound money.

An eloquent orator, Russell defended free trade on many occasions. He supported Democratic measures to lower tariffs on imported raw materials to zero because if American business could buy inputs cheaply, he reasoned, it would make their final products more affordable to more people. In his own words,

If your employer tells you that a high tariff makes high wages, ask him how he proves it. Remind him that in free-trade England, wages are higher than in the protected countries of Europe; that average wages here are lower in protected industries than in the unprotected; that they increased more under a low tariff than they have under a high tariff; and that the Democratic policy of free raw materials means greater demand for goods, and so for labor. Then say to him quietly—very quietly, for he is sensitive on this point—that we have now a high tariff in the McKinley Bill, the highest tariff the country has ever known; that under it wages have been cut down, mills are idle, and men out of work.

The money question was a big issue in the 1880s and 1890s as inflationists in both parties pushed for paper money and subsidies for silver. Russell was solidly and eloquently in favor of a gold standard. When the country entered a depression in 1893, Democrat Russell diagnosed the problem the same way Grover Cleveland did, pointing out that excessive spending, a high tariff, and massive silver subsidies—all enacted by Republicans in 1890—jeopardized both the economy and the currency.

At the age of 19, Russell campaigned for the Democratic presidential candidate Samuel Tilden (a very good man, by the way, about whom I wrote this piece in 2011). Russell’s own political career began when he was in his mid-twenties with election to the Cambridge city council in 1882. Then in 1885, he won his first of four one-year terms as the city’s mayor.

According to the Russell entry in Memorial Biographies of the New England Historic Genealogy Society, he “managed the affairs of the city with great prudence and ability.” In two of his four mayoral elections, no one even bothered to run against him. Cambridge under Russell’s management was regarded by notable observers as the best-run city in the state.

In 1890, Russell won the Massachusetts governorship, becoming the first Democrat to hold that position since the Civil War. Gubernatorial terms back then were a single year in Massachusetts, and Russell won three in a row. Just like he did in Cambridge, he ran a clean administration that, among other achievements, abolished the state’s longstanding poll tax. I would personally have parted company with him on one issue, namely, the state’s first inheritance tax; Russell unfortunately supported it.

There was serious talk in 1892 of putting Russell on the national ticket as Vice President, but that did not materialize. He did, however, over his own objection, earn one vote for President at the Democratic Party National Convention that year. In 1893, he retired to his law practice.

When 1896 rolled around, the Democratic Party was in the throes of a pitched internal battle over the money issue. The gold standard forces of retiring President Cleveland were up against the silver inflationists led by William Jennings Bryan. Russell announced he would be a candidate for President and secured delegates from states up and down the East Coast. He delivered a powerful address at the convention in favor of gold, but he was followed on the rostrum by William Jennings Bryan’s even more powerful “Cross of Gold” speech. Bryan and the silver forces swept the convention, nominating Bryan as the party’s standard bearer in the 1896 election (which Bryan lost to Republican William McKinley in November).

Though he lost the nomination to Bryan, Russell was still seen as a man with a promising political future if he wanted one, if and when the time was right. He left the convention disappointed with the party’s new direction and headed for vacation in the woods of Quebec, Canada. During his first night there, just a week after Bryan’s nomination, Russell died of a massive heart attack. He was just 39, and a husband and father of three young children.

William Eustis Russell was a good man, good enough that his own Democratic Party of today would likely never nominate him for anything. In my view, that’s a posthumous badge of honor.

#####

(Lawrence W. Reed is President Emeritus, Humphreys Family Senior Fellow, and Ron Manners Global Ambassador for Liberty at the Foundation for Economic Education in Atlanta, Georgia. He blogs at www.lawrencewreed.com.)