On the 250th anniversary of the appearance of Common Sense, I decided to give it a long overdue re-examination. I wanted to see if it would “electrify” me as it did so many people so long ago. It did.

Read MoreThomas Paine and the American Spirit

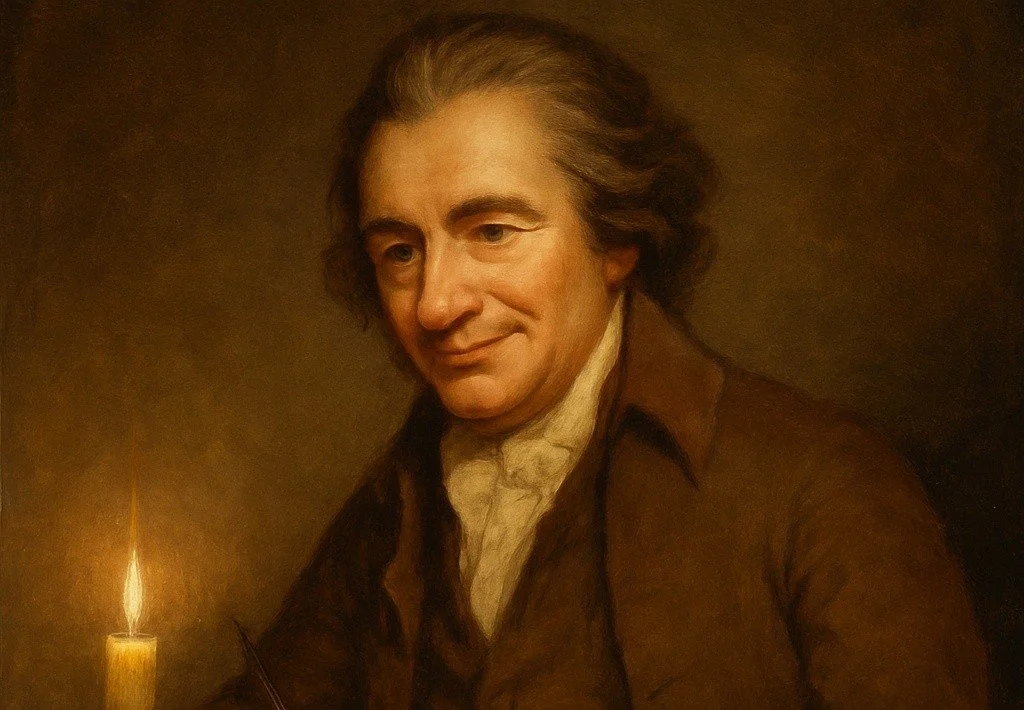

Thomas Paine and the American Spirit

By Lawrence W. Reed

In mid-January 1776, a pamphlet titled Common Sense rolled off the printing presses in Philadelphia. Its language was so clear, its arguments so powerful, its intent so incendiary, that it quickly garnered bestseller status. Indeed, nothing else except the Bible would be more widely read in America over the next six months.

The author of the 47-page tract was identified simply as “An Englishman” but soon everybody knew who it really was—a 39-year-old immigrant from Britain by the name of Thomas Paine. He had arrived in America barely a year before, carrying a letter of introduction from no less an illustrious patriot than Benjamin Franklin. The 20th Century philosopher Sidney Hook would later write of him, “If any man is entitled to be called the Father of American Independence, it is Thomas Paine, whose Common Sense stated the case for freedom from England’s rule with a logic and a passion that roused the public opinion of the Colonies to a white heat.”

Who was this man who burst on the American scene with such force only months before the Declaration of Independence? The first three decades of his life were so unremarkable that nobody foresaw the great fame and influence he would later earn.

Born in the town of Thetford about 80 miles northeast of London on February 9, 1737, Thomas Paine’s first job was making corsets in his father’s shop. In his early twenties, he started his own company in the corset business, but it went bankrupt rather quickly. On the heels of that failure, he lost his wife and first child during childbirth. He later became an “excise officer” or tax collector, a job from which he was fired twice. He avoided debtor’s prison in the spring of 1774 by selling virtually everything he owned.

Benjamin Franklin’s encounter with Paine, however, left a favorable impression. No doubt the old man sensed that this was someone who could become an eloquent ally on behalf of America. When Paine disembarked at Philadelphia on November 30, 1774, he was nearly dead from the typhoid he picked up on the ship. But the letter from Franklin opened some doors. Within weeks, he recovered and began writing and editing for a popular new publication, the Pennsylvania Magazine. From that perch, he watched and learned as colonial distaste for British rule burgeoned into a shooting war.

The fateful year of 1776 began with most Americans still hoping for a reconciliation with the mother country. Only a handful, quietly and privately for the most part, favored the treasonous notion of separation. In early January, Paine finished up his pamphlet that would tip the balance of opinion in favor of separation, even if it required a war to accomplish it.

Conventional wisdom holds that when the Declaration was issued in July 1776, a third of Americans supported independence, a third opposed it, and a third hadn’t yet made up their minds. That’s purely a guess, as the first public opinion polling wouldn’t occur for another half-century. Whatever the sentiments were in 1776, no one disputes that Paine’s eloquence moved Americans dramatically. It crystallized the case for an independent America. It emboldened patriots. It electrified the debate from New Hampshire to Georgia.

On the 250th anniversary of the appearance of Common Sense, I decided to give it a long overdue re-examination. I wanted to see if it would “electrify” me as it did so many people so long ago. It did. I offer the reader a selection of passages that illustrate the power of Paine’s pen, beginning with this one:

Some writers have so confounded society with government, as to leave little or no distinction between them; whereas they are not only different but have different origins. Society is produced by our wants, and government by our wickedness; the former promotes our happiness positively by uniting our affections, the latter negatively by restraining our vices.

These are not the words of an anarchist, but of a man whose views would place him today in the camp of limited-government libertarians or “minarchists.” Paine believed that “government even its best state is but a necessary evil; in its worst state, an intolerable one.”

In Paine’s estimation, monarchy was a prime example of government “in its worst state.” He commenced his case against it by citing Samuel, the last of the judges who presided over the ancient Israelites. When the people asked for a king, Samuel warned them that a king would “take your sons and make them serve with his chariots and horses,” and “take the best of your fields and vineyards and olive groves and give them to his attendants,” among other evils. “When that day comes,” admonished Samuel, “you will cry out for relief from the king you have chosen, but the Lord will not answer you in that day.”

Paine is sometimes tagged as an atheist, but he was never one. He was a Deist, meaning he believed in the existence of a Creator but one who didn’t intervene in the affairs of men. In his later years, he criticized elements of Christianity but never argued that life or the physical universe were accidents. And he thought Samuel was precisely right when he told the Israelites to reject monarchy, though they sadly didn’t listen.

The hereditary feature of most monarchies, Paine reasoned, simply added insult to injury:

For all men being originally equals, no one by birth could have a right to set up his own family in perpetual preference to all others forever …. One of the strongest natural proofs of the folly of hereditary rights in kings is that nature disapproves it, otherwise she would not so frequently turn it into ridicule by giving mankind an Ass for a Lion.

Divine right was neither the origin nor a proper justification of monarchy in Paine’s view. If we could lift the veil of mystery and legend, he wrote, “we should find the first of them nothing better than the principal ruffian of some restless gang, whose savage manners … obtained him the title of chief among plunderers.” My favorite line is as definitive a judgment on one-man rule as any ever written:

Men who look upon themselves born to reign, and others to obey, soon grow insolent; selected from the rest of mankind their minds are early poisoned by importance; and the world they act in differs so materially from the world at large that they have but little opportunity of knowing its true interests, and when they succeed to the government are frequently the most ignorant and unfit of any throughout the dominions.

Reviewing British history, Paine concluded that kings brought conflict and wars that republics such as that of Holland at the time were able to avoid. If a government cannot or will not foster peace, what good is it? he asked. Far more “natural” to the affairs of men than arrogant kings is wise and reliable law that arises from the consent of the governed:

But where, say some, is the King of America? I’ll tell you. Friend, he reigns above, and doth not make havoc of mankind like the Royal Brute of Britain…[A]s in absolute governments the King is law, so in free countries the law ought to be King; and there ought to be no other.

Though Paine’s impact derived from his writing, he clearly believed that the time for writing was over. He urged Americans to put down their pens (and attempts to reconcile with Britain) and take up arms. The cause of liberty fully justified force against force:

O ye that love mankind! Ye that dare oppose not only the tyranny but the tyrant, stand forth! Every spot of the old world is overrun by oppression…O! receive the fugitive and prepare in time an asylum for mankind.

In calling upon Americans to set patience aside and revolt against tyranny, Paine argued that the world might well be transformed as a result. One burst of eloquence near the end of Common Sense would stir the blood of American patriots then and ever since: We have it in our power to begin the world over again.

When the Second Continental Congress approved the Declaration of Independence six months after Common Sense blazed the trail, Thomas Paine could rightfully claim the right to be its intellectual godfather. Only days before, he was the first to suggest that if independence was declared, the new nation should call itself the “United States of America.”

Late in 1776 as defeats on the battlefield prompted spirits to waver, Paine rallied Americans with powerful essays under the title, The American Crisis. He began that series with these famous and stirring words:

These are the times that try men’s souls. The summer soldier and the sunshine patriot will, in this crisis, shrink from the service of his country; but he that stands it now deserves the love and thanks of man and woman. Tyranny, like hell, is not easily conquered; yet we have this consolation with us, that the harder the conflict, the more glorious the triumph.

Paine lived another 33 years, passing away in 1809 at the age of 72. And what an eventful three decades it was! In that time, he defended the early stages of the French Revolution in another famous pamphlet titled The Rights of Man. He was even made a citizen of France and was elected to the French legislature. When the radical Jacobins under Robespierre hijacked the Revolution, he narrowly escaped the guillotine. Around the same time, he fell out of favor with many leaders of the new America, who saw him and another of his essays, The Age of Reason, as too radical on both politics and religion.

Irrespective of later controversies, Thomas Paine’s legacy of passion for American liberty was firmly secured in 1776 with the pamphlet adorned by the simple title, Common Sense. May its spirit live forever in the hearts of all patriots!

For additional information, see:

Thomas Paine and the Promise of America by Harvey J. Kaye

How Americans Learned to Love Thomas Paine by Jennifer Schuessler

Thomas Paine and the Clarion Call for American Independence by Harlow Giles Unger

Thomas Paine: A Political Life by John Keane

Thomas Paine: Words That Sparked a Revolution (video)

(Lawrence W. Reed is President Emeritus, Humphreys Family Senior Fellow, and Ron Manners Global Ambassador for Liberty at the Foundation for Economic Education in Atlanta, Georgia. His website is www.lawrencewreed.com.)